Fact vs. Fiction

One of the more active forms of debate in many Sci-Fi modeling forums is the "reality" of many of the spaceship designs we have come to know and love. It can also appear, particularly to those just on the periphery of this niche in fandom, a bit childish and inane. Still, particularly in film where these ships are actually seen - inside and out, there is a certain fan that wants to know exactly how it works and how everything fits. Of course rarely does this actually matter to the actual producer of the imagery since what they really want is essentially an aesthetic effect. It isn't a government contract for an actual working model!

I have also found myself caught up in this kind of speculation, wasting a lot of time on practical configurations, mission profiles, fitting internal spaces, counting pixels, and estimating sizes. What makes this rather silly is that I am not an aerospace engineer, so what do I know about the minimum thickness of a spaceship pressure shell or the required amount of radiation shielding. I also am quite aware of the fact that the original producer may not really care.

Recently I found an old copy of

Air & Space magazine which had an engineer's perspective on some landmark Sci-Fi ships. Another book I took out of the bookcase was the

Starflight Handbook which goes into great technical detail about the physics of distant space travel. This rekindled a topic that I hadn't gotten to write about during my previous spaceship posting. While I'm no expert, I do know enough science to know that some things do bug me when I see them. On the other hand, reading up on these bugbears allowed me to see that they may not be as heinous as one might think.

You don't need no stinkin' intakes...

Ever since

Star Wars, it seems that there isn't a space opera that doesn't have the one-person fighter, and that fighter has these huge intakes. The question is that in space, what are they

intaking? Some spaceship designs even incorporate intakes into large vessels. Various Star Trek designs incorporate slots and other "flush" vents as if something was meant to pass through them (curiously the main thing that is understood to be a necessary intake, the

Bussard collector, doesn't look much like an intake at all!).

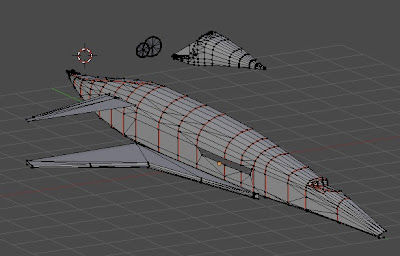

The argument is often made that these designs are meant to work in an atmosphere as well as space, and as such intakes make some kind of sense. But then you get odd contradictions, namely that to operate at high speeds in a dense atmosphere you need to be streamlined or suffer very high stresses, and yet given the tendencies to make designs very "greeblied" the surfaces of these ships are not suited for atmospheric travel at all.

I suspect the intakes are there because they are familiar with our idea of fighter design. They convey a sense of power and energy. While we may all have flown in jet aircraft, the fighter jet conveys a sense of power that is visible in the proportion of the intakes and the exhaust to the overall size of the aircraft. One cannot just dismiss that idea from a design of a fictional fighting craft. A fighter plane is basically an engine with wings (in fact in many designs, fuel is such a small part of the design that many fighters aircraft are said to be in a fuel emergency right after take off).

Intake/Exhaust to general aircraft shape ratio has its limits as far as looking "fast" as the real life Caproni Stipa or Flying Barrel illustrated (another example is the McDonnell "Goblin")

If one looks at the rocketship designs from the 30s one can find them full of exhaust manifolds and long curved stacks that were prominent in airplanes and sports cars at the time. The ring of rocket exhausts around Flash Gordon's rocketship look a lot like the ring of cylinder exhausts you would have found on an aircraft radial engine at the time. I'm sure that in that time period, the look of huge aviation and automotive engines conveyed that same sense of power that huge intakes and exhausts do to us now.

...or do you need the intakes after all

One of the biggest problems in affordable space flight is the ratio of propellant mass to total mass. Currently, the requirements are well above 90%, which is why single stage to orbit is so darn difficult. One of the ideas to solve this problem would be augment the propellant with air in the lower atmosphere. These proposed boosters would actually have what look like oversized jet engines. This airflow to the combustion engines is meant to lower the amount of oxidizer and propellant needed as this airflow mass is accelerated along with fuel.

My daydream of an Aries type orbital shuttle being launched after assembly by an air augmented "Nova"-like booster like some gigantic shuttlecock.

The

Profac or propulsive fluid accumulator was meant to be an orbiting fuel collector. The basic idea is for an active orbiter that would skim the upper atmosphere and with its intake scoop out oxygen and nitrogen to preclude the high costs of actually launching this material into space. While it's main propulsion system to compensate for drag would use ion power, the design would contain conventional boosters that could make use of its haul for fuel for more energetic boosts.

Another idea is to use a space based system to

beam microwaves or lasers to your ship. The ship would use the energy to ionize gas and so create thrust. In some cases (not all) such a ship would also use intakes to collect air as it accelerates in the lower atmosphere. The advantages of such a ship is that it limits the propellant requirements to what would be needed to reach final velocity outside the atmosphere (but note, it still wouldn't need oxidizer as the energy would come from the beam, not the propellant).

All starship fans know of the

Bussard Ramscoop Ship. The premise is akin to a ram-jet engine. Normally a jet engine uses sets of compressor blades to gather and compress air for combustion. If on the other hand the engine is moving at a certain rate of speed, the mere act of forward motion would allow it to collect and compress the necessary air. Similarly while there isn't enough free hydrogen to easily run a rocket in space, given enough speed, a ship could cover enough volume of space that it could conceivably collect the necessary fuel from interstellar space. To do this it would need an intake. While a practical intake would have to be hundreds of kilometers wide (which from the point of view of an illustrator, a bit of a problem), this intake may be made from magnetic field lines instead of being physical. Designing a ship with intakes therefore may not be that crazy after all.

The Center of Gravity

One of my pet peeves about some designs is the way the thing appears to balance. A classic example is the

USS Enterprise itself. A casual look at the position of the impulse engines suggest a fairly high position for applying an impulse. Unless the warp engines are rather heavy, the impulse engines would tend to flip the ship head over heels (Of course the impulse engines themselves may also work in some very weird way).

Many ships for the purpose of appearing rakish or sleek do seem to make use of a certain off-center look. The appearance is sometimes based on the look of sports cars, which of course have different balance issues since they are grounded on their wheelbase. Even aircraft can appear to have off center lines, but the imbalance is an illusion as aircraft are not just balanced against gravity, but centers of lift and drag (which can vary with speed).

Asymmetry is possible and interesting to look at, but I feel (and this is really personal) it needs to have some aspect to the ship to justify some form of balance (i.e. the centers of mass, lift, thrust, drag, etc., should match).

The Blohm & Voss BV 141, perhaps the most asymmetric aircraft ever flown. Another notable asymmetric aircraft was NASA's AD-1 Oblique wing concept and an unfortunate F-15 that lost its wing and yet still managed to land safely.

Is power an issue?

On a personal point, I can't bring myself to have too much of an issue with power, at least as far as an artistic portrayal of a spaceship is concerned. The fact is that the amount of power required to move anything over the vast distances of space is far beyond most of our means (at least in a reasonable time for the plot). For the purposes of plot, whatever that power source is, the power source is both very powerful and very small.

That said, given that the ship may need some fantastical source of power, how should that be portrayed? Sometimes it is shown as huge engine bells exhausting white light, or it could be the sheer size of the engine assembly itself. Paintings by Robert McCall or others may portray bright streaks of white, red or yellow to indicate the propulsive energies involved (

the cover of the original Star Trek novelization show streaks of flame shooting out of the Enterprise's nacelle's and hull).

The funny thing is that the reality is probably much less dramatic. An engineer in the Air & Space article noted that while he thought the

Discovery from

2001: a space odyssey was among the most realistic designs shown on film, the engine bells were just much too big. Our impression of big rocket engines comes from the huge Apollo F1 engines which you can see at the Smithsonian, but these engines were designed to operate in the atmosphere. In space these engine bells would have been substantially smaller.

Another decrease in drama is that engines don't have to fire constantly in space unless you are changing direction or speed. We have gotten used to idea that if "it's moving" then "the engine is on" from our earthbound experience, but really, once the Galactica is in motion, it's in motion until some external force acts on it.

This means that the reality is that engines can be fairly small in appearance and hardly ever on, so a ship in space looks pretty inert. On the other hand, there's nothing like engines at full thrust to suggest impending adventure. The fastest moving object in space currently is Voyager 2, and it doesn't look substantially different from the one hanging in the museum.

The Details

Finally the thing that often gets in the way of taking some design seriously is the details. Sometimes just basic physics, for instance why don't ships have reaction control systems. Well, it has been interesting to note that they are not always totally absent. The original Enterprise had no visible RCS anywhere, but this was rectified when it was revamped for the "

Motion Picture" version. Still, they are often missing in many popular designs and artwork.

Fictional RCS (L-R):2001(pod), Star Trek, Space 1999, Galactica (reboot), Hyperdrive

It is actually possible to control attitude without reaction jets and this is with internally mounted gyroscopes(

control moment gyroscopes). Anyone who has played with gyroscopes has noted their ability to react against changes in orientation. This is the way the International Space Station controls its attitude.

Another interesting aspect of real spacecraft not often shown is that the vacuum of space actually makes it very difficult to loose heat. The active use of electronic equipment and power generation will create waste heat which if allowed to build up could be catastrophic (and that is without even mentioning the waste heat a compact source of fantastic energy must have). While designs do sometimes appear with solar panels, they are not often shown with corresponding radiators. This is perhaps because we (i.e. the general public) don't often associate radiators as a vital aspect of spaceflight, although it is sometimes some of the most visible parts spaceships taking on the appearance of fins and winglike appendages

Stanley Kubrick deliberately removed the radiators from the original design of the

Discovery in

2001 in spite of the fact that such a nuclear powered ship would require huge radiators. Kubrick was concerned that the spacefaring ship not be identified as having fins or wings like so many earlier science fiction film rockets.

The need for some form of radiators can be taken to heart by all those who want wings of some sort on their vacuum bound spaceships. They are not wings, they are radiators. I always thought that was what those big black panels on Tie fighters were anyway (regardless of what those "technical" references might say).

The list of details can go on and on: Where is all the propellant mass stored? Where's the shielding? Where's all the food and water? Where's the head?

So how does fact relate to fiction

Curiously much of what we can consider lapses in design can be explained away in some manner shape or form to at least a minimal extent, and not always with technobabble. Sometimes it may be reasonable for a ship to lack RCS or have intakes. As mentioned in a previous article, the up/down consistency of a ship in space may be necessary to keep the crew from getting sick. An apparent imbalance in some design may be justified by re-interpreting what appears to be the case, such as the way masses may really be distributed in the design, at least as far as the original designer was concerned. It is also important to note that any society that can propel a spacecraft across light years probably knows how to deal with artificial gravity, radiation shielding, and high speed particle erosion.

Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind is that these are not real ships. The reason they look the way they do is to convey a feeling or an overall atmosphere for a story. They exist to convey characters from point A to B, or place them in a setting that is outside of our general experience. These things need to be by definition fantastic. Our fascination with these "spaceships of the mind" is in how wonderful we find them. Their limitation to facts and science is only so far as their creator's attention to the facts help suspend disbelief, which is the key point of a fictional ship. After all is it any more or less believable that we may someday live and travel far and wide through space versus the idea that three women, a culinary student, a masseuse, and one with a somewhat checkered working status, can afford to live in a large three bedroom Manhattan apartment with cathedral ceilings and a large balcony (now that's fiction).

End Note

Just to make a note of some of the references used which can be interesting points of departure from this article. For one thing a reader may refer back to the

previous spaceship design articles and the final

reference posting created for it (particularly good is

Atomic Rocket). The original article that started this off was

"Planet of Origin: Hollywood," by Dennis Meredith, Air & Space Magazine, 4:1:pp80. Another handy reference in the bookshelf was the

Starflight Handbook by Eugene Mallove & Gregory Matloff (Wiley Science, 1989). An interesting web site that I came across while looking up info on

Bussard Ramscoops and

Profac was

This is Rocket Science (my original reference was my old copy

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Space Technology, Kenneth Gatland et.al. 1981). While there is always

The Physics of Star Trek by Lawrence M. Krauss (Harper Collins 1995), this time I spent more time with

The Cosmic Dancers by Amit Goswami (Harper Row 1983). The most comprehensive collection of how Hollywood gets all this stuff wrong on the web is probably

Phil Plait's Bad Astronomy.

I guess my own final note is a weird sort of recognition that the articles in my old books that date back 20-30 years still fair pretty well in the realm of speculative spaceflight and rocketships (yes there's stuff that's missing, but still...). Is that good or bad?