In preparation for Arisia 2013, I've started to look for a simple model that will fit in 2 pages and be built (or at least mostly built) in about an hour. As usual, foregoing the Borg cube because it's a little too quick, trying to find both interesting

and easy is proving rather difficult. So currently I've been following several tracks simultaneously.

The candidates are:

- The Last Apollo, the CSM for Apollo-Soyuz

- The Narcissus, in a greatly simplified format

- The Dark Star, perhaps including bomb 20

- The LIS space pod, pretty orange

- C-57d, a simple saucer

- General impression of a typical London police phone box from the 60s

For the winner, I'll have to get back to you later, but for now I figure I could pass on some insight into kit design and some Blender paper unfolding foibles I've run into so far.

Keep it simple

The object of using Blender is to make creating parts for the kits easier, not creating a 3D model of the object. Thus there are a couple of important things to keep in mind: first, I don't need the whole object, and second, the fewer the polygons, the better.

|

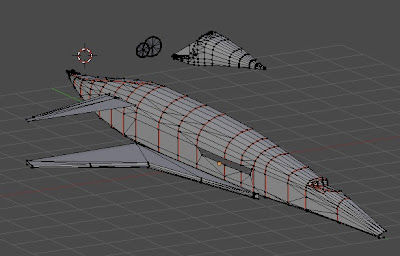

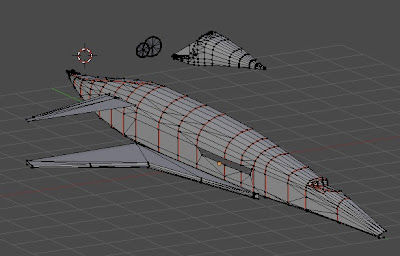

Port Engine for Simple

Nostromo model. No starboard

engine drawn since it is identical.

|

Why don't I need the whole object? Often the subject express some sort of symmetry. Now for some subjects, the shape is simple enough that getting the whole shape done when modeling is OK. Take a missile fuselage for instance. It is relatively easy to create a pointed cylinder so, one just does it, but consider the Narcissus for instance, and more specifically the engine assembly. In the simple version I was working on, it was easy to get a lot of the shapes done based on cube primitives, but why build 2 engines; the left is just like the right. So you create one, print twice. A more subtle situation would be the rear stabilizer on the Buck Rogers cruiser where the left is the mirror of the right. This is easily rectified after the part is rendered, just copy and create a mirrored rotation. So for creating a bilaterally symmetrical subject, you really only need one half. Given the quirkyness of the Blender unfold script, reducing polygon count by half this way is a pretty good thing.

|

Only starboard section designed as port side parts will only be mirrored from starboard. While the model shows a relatively high number of polygons, it is substantially less than for a high quality model designed for CG illustration.

(red lines indicate marked seams for part cut)

|

|

Bad unfold render for parts for a C57d

attempt. Parts here should have been

circular and symmetric. Note how the big

part on left is not only squished, but also

wider on left than right. Also note the many

small identical parts which should have

been one large piece in spite of marked

seams on original.

|

Why keep the polygon count low? Well, there are a couple of reasons. One of the critical ones specific to Blender, although I wouldn't be surprised if it applies to other unfolding scripts as well on different platforms. Blender unfolding is quirky. I've noticed that sometimes, if there are just too many odd folding operations on high polygon counts, it just doesn't go. Other times it just does a very weird thing where the packed parts are distorted as if processed through a flawed lens. This last bit is a very frustrating problem since it seems that whatever that flaw is, it is deep in the file and difficult to correct by simply simplifying the model (I suspect it is really the result of some corruption of the actual file, such as a hidden vertex or edge mucking up the works). Another reason is that the script sometimes does some odd seam splitting leaving you with a great many odd shapes and a bit of a jig saw puzzle problem. If you have a lot of polygons, these may end up looking alike, making it rather tricky to put humpty back together again, but if you have few, these polygons will be more unique. Note low polygon count doesn't necessarily mean keep it under 20, it just means you should not be creating objects with complicated curves with thousands of facets as people who create 3D models for image work create. CGI artists are trying to get these objects with faceted surfaces to blend neatly into smooth forms, whereas paper bends naturally so we don't need to be as worried about that (actually CGI models achieve a similar effects using splined surfaces, but that's another story).

Another reason for keeping polygon counts low is since you are creating a part to cut out, you don't want a part that is particularly complicated for cutting. Keep this in mind when deciding where the seams should go.

Another aspect of keeping it simple is breaking up the project into sub-assemblies. I was working on a particular subject which unfolded rather nicely (in fact given how complicated the original subject was, I actually was surprised it worked at all). The only problem was that I had so many parts, figuring out what went where would have been extremely time consuming. So instead I broke the original file into smaller constituent parts. This allowed me to only unfold the parts I could deal with at one particular time and actually worked nicely for creating the design track for a project (main body, engines, wings, gear, optional items, etc).

|  |

More detailed Nostromo Engine Assembly

This is still meant to be for easy assembly

|

The Orion Engine Assembly (stbd)

This is actually in 3 parts, exhaust cone, internal supports, external shell

|

Future things to still work on

I still haven't devoted time to creating textures for the models. On the one hand, this isn't really necessary because, again it isn't meant to be seen on screen. On the other hand, figuring how to place markings on a blank part can be very difficult and requires careful observation of the superimposed model on the background plans.

Main thing now though is to get some stuff finished so I can post the parts and instructions. Oh, btw, leaning to the Apollo. Already built a test version, and while it could use adjustment, it isn't half bad and still a very simple build.

No comments:

Post a Comment